Beaconing Morse with a Si5351 Clock Generator

I bought an Adafruit Si5351 breakout a while ago and I finally thought I’d sit down and play with it. Because I needed a microcontroller to drive the thing, I hooked it up to a board running CircuitPython (yeah, I get a lot of stuff from Adafruit). Now, the genesis of this short hack was that I’ve been studying a lot of morse code (“CW” in the lingo) and I felt that I lacked a gut feeling for what the CW mode on the radio does. Intuitively I understand that there’s a signal that’s being turned off and then on. And I understand, roughly, how both amplitude and frequency modulation work, even if I don’t know all the details about how either is decoded. But is morse just a 700 Hz tone that’s then (say) amplitude-modulated onto a carrier, or is something else going on? What would happen if I just generate a radio frequency sine wave and then turn it off and on?

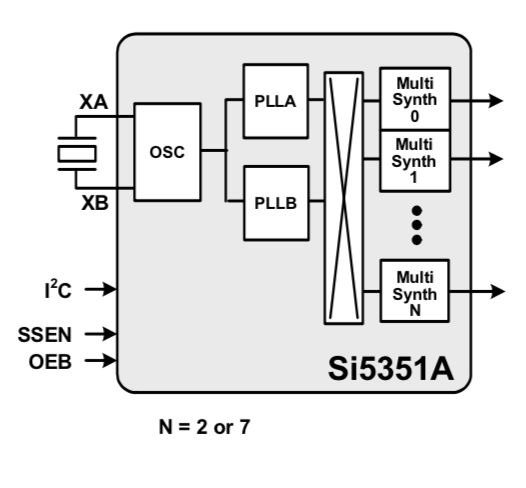

Enter the Si5351: its datasheet proclaims “I2C-PROGRAMMABLE ANY-FREQUENCY CMOS CLOCK GENERATOR + VCXO”. Any frequency you say? Reading the datasheet shows that there’s essentially two stages:

The chip has a 25 MHz external crystal oscillator connected. The oscillator is multiplied in one of two PLLs. Then the signal is routed out to one of the clock outputs. Here the frequency is divided down to it’s final output value. Choosing the correct integer (or fractional) numbers for each stage lets you select a wide range out output frequencies.

The following code sets up the Si5351 to output a (roughly) 7.075 MHz signal (25 MHz * 15 / 53). Then, in a loop, the output is enabled and disabled1 depending on the item being sent (dot or dash). By the way, there’s nothing special about that exact frequency other than I wanted something in the cw portion of the 40m band.

import board

import busio

import adafruit_si5351

import time

# init the i2c connection with the si5351 chip

i2c = busio.I2C(board.SCL, board.SDA)

si5351 = adafruit_si5351.SI5351(i2c)

# config PLL and clock outputs on the si5351 chip

si5351.pll_a.configure_integer(15) # 25 MHz * 15 = 375 MHz

print('PLL A: {0} MHz'.format(si5351.pll_a.frequency/1000000))

# config clock output & divider

si5351.clock_0.configure_integer(si5351.pll_a, 53)

print("Clock 0: {0}mhz".format(si5351.clock_0.frequency / 1000000))

dit = 0.060 # seconds

dah = 0.180

space = 0.120

interword = 0.360

callsign = "-.-/-../----./-.-/.---/...-x" # KD9KJV

# WPM = 20

while True:

for c in callsign:

if c == ".":

si5351.outputs_enabled = True

time.sleep(dit)

si5351.outputs_enabled = False

time.sleep(dit)

if c == "-":

si5351.outputs_enabled = True

time.sleep(dah)

si5351.outputs_enabled = False

time.sleep(dit)

if c == "/":

time.sleep(space)

if c == "x":

time.sleep(interword)

time.sleep(interword)

si5351.outputs_enabled = False

I loaded this into the Gemma M0 and used a random-wire antenna, that is to say I grabbed the first 6 inch wire jumper that I could find. My radio, an Icom 7300, was not connected to an antenna at all. Over the very short distance of about 2 feet, it could still clearly receive the morse coming from the chip. Even a miniscule signal, the Si5351 outputs about 3 V, was detectable.

Here’s a video of the radio receiving the morse transmission. Be sure to turn sound up to see that you can clearly copy the letters.

This was all a pretty rough hack but it is remarkable that so little is required to send morse. And it answers my original question. There’s really nothing else going on with CW. We are really just turning a carrier on and off. The sound that the radio is making, and I looked this up, traditionally comes from a local BFO or beat frequency oscillator. And this does what the name implies, it combines the output of a local oscillator with the incoming signal so that their difference is an audible 700 Hz-ish tone. But it doesn’t change the fact that the RF coming in is really just that carrier frequency. There’s no additional magic going on.

-

The timing of morse is a little fiddly, but here’s the breakdown for the interested. At 20 words per minute, a dit (dot) is 60 msec long, a dah (dash) is three times that, 180 msec. After each element, within a character, (e.g. between “.” and “-“ in “A”) there’s a time of one dit, 60 msec. After each letter, there’s an additional 2 dits worth of time (totaling three dits). Similarly, at the end of a word, there’s an additional 6 dits of time (totaling 7). ↩